Hello Earthlings.

I was inspired to make this unedited mosaic from 12 images taken by Percy on Sol 178 (earth date August 20th, 2021) this week. Percy is hot on the rock hunt(!) Determined to find a sample that won’t crumble before capture, Perseverance is checking out rock after rock after rock looking for only the best. I wonder what’s on Percy’s Rock Hunt Mixtape? Maybe LMK ok?

I hope you find your rock//stone//sample spots soon Percy!

let’s go

volume (5):

The Milky Way has a fractured arm - and there might be more(!)

Isn’t it kind of crazy that we have never even seen our home galaxy the way we have seen some distant neighbors?

When you look up at the stars in the night sky they appear fixed in a way. They might vary slightly in brightness, but they all seem pretty much equally distant from us. They do seem to move across the sky in a predictable pattern year after year, but with just the naked eye, it is easy to think ah the stars must move in the sky because Earth rotates. And that’s exactly what early star-studiers thought. Earth was the center of the universe, and everything, all the sparkles in the night, must move according the Earth’s movements.

Without some sort of technology (i.e. telescopes, photography, etc), the naked eye can see about 6,000 stars in the sky (and while that is certainly quite a few its quite a tiny percentage of our galaxy’s estimated 100 - 400 billion stars) and only three galaxies(!). It was assumed that all the stars were part of the same mini universe, already called the Milky Way thanks to the Ancient Greek myth about the goddess Hera squirting her breast milk across the sky… So glad that stuck…

Early star-studiers using early telescopes observed what they referred to (incorrectly) as ‘nebulae’ or ‘nebulous smears’ in the night sky. They thought they might be cloudy regions of the Milky Way. There’s actually an incredible doodle (see below) by Lord Rosse who built a “large” telescope in 1845 and was able to decipher two different types of these so-called ‘nebulae’ (elliptical and spiral).

During his search for comets from 1771- 1784, Charles Messier compiled a catalogue of a number of bright ‘nebulae’ - many of these objects, known now as Messier Objects are understood to be galaxies.

I’m sure the idea floated around, maybe since ancient history when the first star catalogues began to take shape, but isn’t it kind of wild that it wasn’t until the late 1920’s that we discovered our galaxy was just one of many? That’s barely one hundred years ago(?)! Remember our variable stars, specifically the Cepheids? It was Edwin Hubble in 1924 using the biggest telescope at the time (the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson) observed Cepheids from what is now known as the Andromeda (not nebula) Galaxy and the Triangulum (not nebula) Galaxy. He compared these Cepheids to those he and others had observed in the Milky Way and determined that some stars were without a doubt too far away to be part of our home galaxy. These stars were part of their own galaxies and ours was one of many.

Today, thanks to an incredible squad of space telescopes from all across Earth, we can tell a lot more about these galaxies of stars far far far away.

What’s harder still, is to look inward at our own galaxy. It’s like you’re on a looping roller coaster in the middle of clouds, there are 100-400 billion fireflies moving in an unknown formation, some of these fireflies don’t even light up in ways you can see with your eyes and you are supposed to make a bird’s eye view map of the fireflies.

Astronomers have for many years been plotting the movement of stars in the Milky Way hoping to gain insight on the shape, nature, and evolution of our home galaxy. No sky survey to date has been as prolific as the European Space Agency’s GAIA. Gaia has observed the motions of about 1.7 billion stars (still only about %1 of the stars in the galaxy, can you even believe that(!)?) in the Milky Way since launching in 2013. Gaia has been measuring positions, parallax, proper motion and time series photometry of thousands of variable stars in the Milky Way. Gaia is expected to observe hundreds of thousands of variable stars in the Milky Way(!).

By looking at the motions of all these stars in our galaxy as well as their distances and relative positions on the galactic plane, astronomers can start to put together a picture of all the moving fireflies.

One of the details that characterizes spiral galaxies is how tightly wound their spirals are. Another is how many “arms” they have in their spiral. In the current imagining of the Milky Way, the Sagittarius Arm is the closest spiral arm inward from the Sun. An important property of spiral arms is how tightly they wind around a galaxy. This characteristic is measured by the arm's pitch angle (a circle has a pitch angle of 0 degrees, as a spiral becomes more and more open, the pitch angle increases).

When astronomers measured new data from Gaia looking at groups of young stars they discovered a new feature previously unnoticed in the Sagittarius arm of our home galaxy. Most models of the Milky Way suggest that the Sagittarius Arm forms a spiral that has a pitch angle of about 12 degrees, but the newfound structure has a pitch angle of nearly 60 degrees (!).

What’s interesting to me is that the “new” feature includes some very old suspects - the Lagoon Nebula (Messier Object 8), the Eagle Nebula (M16), the Omega Nebula (M17), and the Trifid Nebula (M20). All celestial objects, of course, from the Messier Catalogue of the late 1700’s.

Some of the stars from these exact nebula were the ones astronomers used back in the 1950’s to infer the existence of the Sagittarius Arm to begin with(!). Now there have been plenty more stars observed to infer the existence of the Sagittarius Arm but the picture remains ever evolving of our home galaxy.

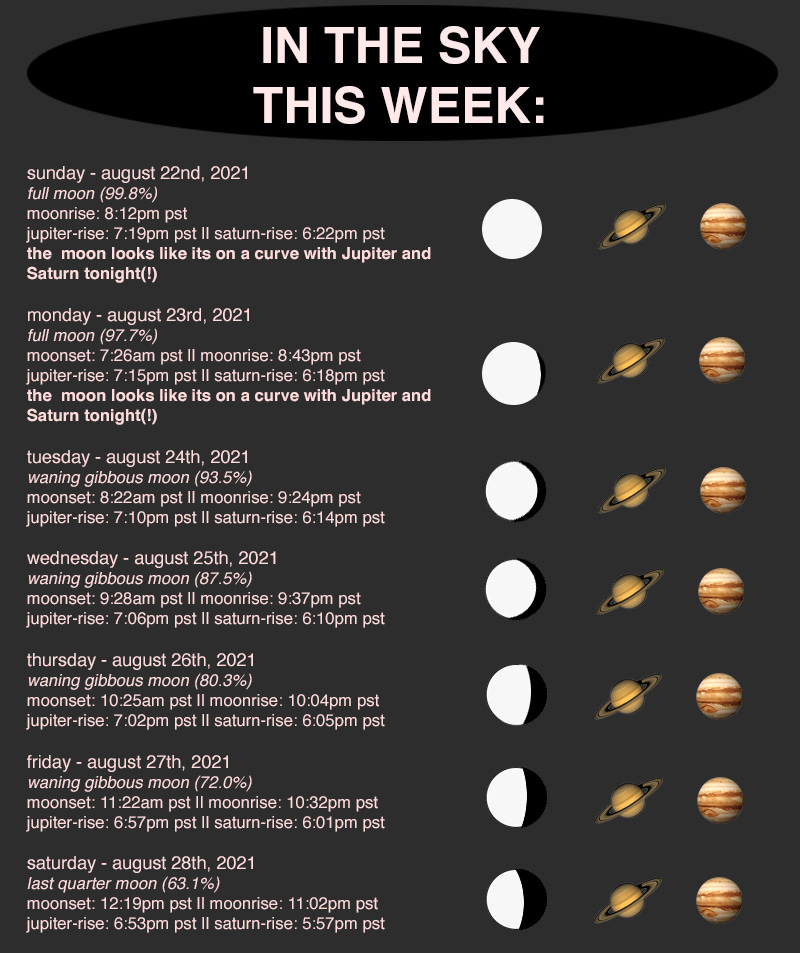

Moon Pic of the week (!)

Don’t Miss Out (!)

“The Milky Way is nothing else but a mass of innumerable stars planted together in clusters.” - Galileo Galilei